Visually breath-taking, morally reprehensible and mechanically backwards, Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon: Wildlands can’t decide what game it wants to be. In one moment, it’s a squad-based tactical shooter in a bizarre and bleary approximation of Bolivia; in another, it’s Just Cause. But between those two polar experiences, there’s very little to it.

The elevator pitch for Wildlands is astounding: an open and hostile tactical playground geared towards co-op. And that map is huge-one of the biggest I’ve seen in a game like this. I could spend hours taking in its mountains and valleys. But this is Wildlands, and it never stops moving. The map is littered with bases to raid, occupied villages to liberate, communication outposts to shut down and resource convoys to steal. There are so many hundreds of things to do that the space between them becomes a static waste.

And the basic ways you interact with the world-the guns you fire and team you lead-are all just fine. AI is inattentive and slow on both sides, but squadmates are left with a sort of omnipotence in the right hands. It makes the tactical sneaking elements more than a little repetitive, but there is something to be found in the mass-murder antics of the sync shot. The guns have a satisfying kick to them, and the hit marker (as sacrilegious as it is in a tactical game) might be the most satisfying since the dawn of Modern Warfare.

Wildlands’ exhaustive equipment list is all-encompassing and varied, and most weapons are further customisable to suit different situations. Tearing weapons apart and building them up with new attachments has become a mainstay of the Ghost Recon franchise, but it’s still refreshing to see an open world game with such a large arsenal.

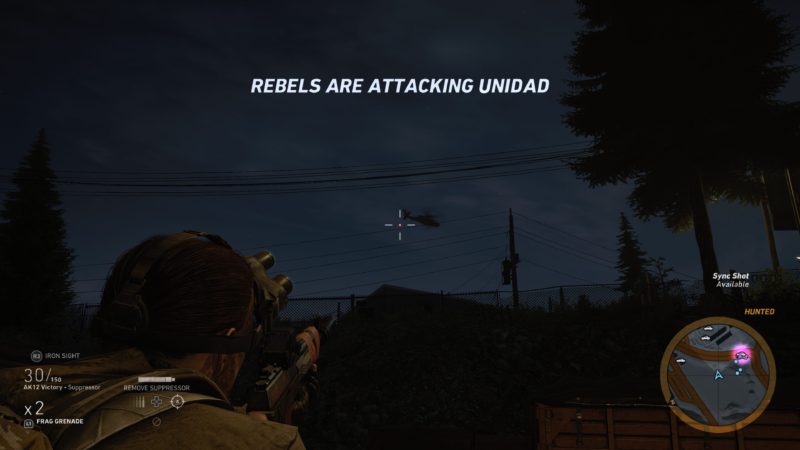

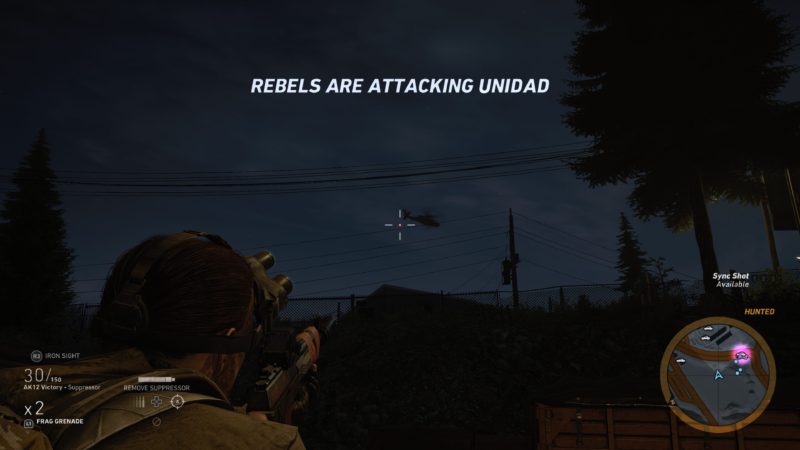

Similarly utilitarian are the driving and flying. The array of cars, bikes, quads, planes and helicopters will get you from point A to point B effectively enough, but only if you stick to the roads; the topography of Bolivia is such that driving off-road is nothing short of a nightmare. And so empty are the skies, so gracefully stable are the air vehicles that Ubisoft simply added near-unavoidable anti-air emplacements to make sure you found the ground-and a few more people to shoot.

The Ghost Recon name feels vapid when attached to Wildlands. It loses all relevance on a game that is so devoid of meaning and precision. Metal Gear Solid V took the series’ long-established stealth mechanics and built its open world around them. Wildlands does the opposite, taking what could’ve been in-depth tactical combat and diluting it in the mass-market Ubisoft formula. Maybe it shouldn’t have come as a surprise given the trajectory of the last few Ghost Recon titles, but that name still carries something, surely?

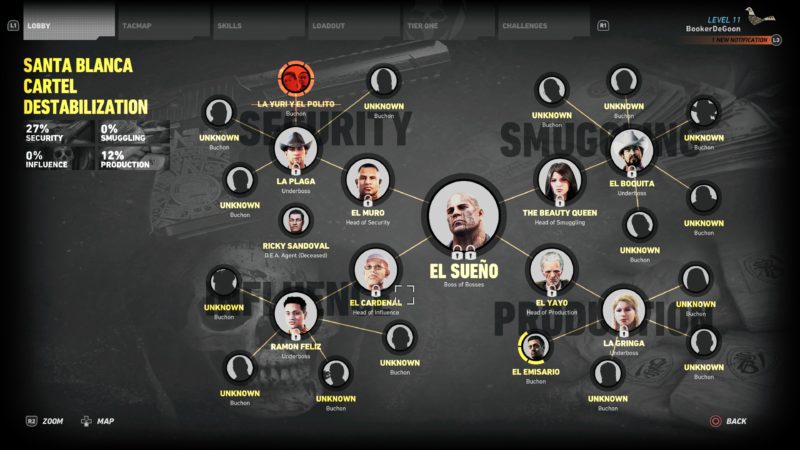

Nothing illustrates Ubisoft’s milquetoast approach to this game more than its CG intro. El Sueño, leader of the Santa Blanca cartel and the game’s largely absent antagonist, monologues about the founding of his narco-state. It’s an almost comical attempt at empathy and does a disservice to an already narratively-handicapped game. By hour fifteen, I had blotted out the majority of the game’s exposition with podcasts.

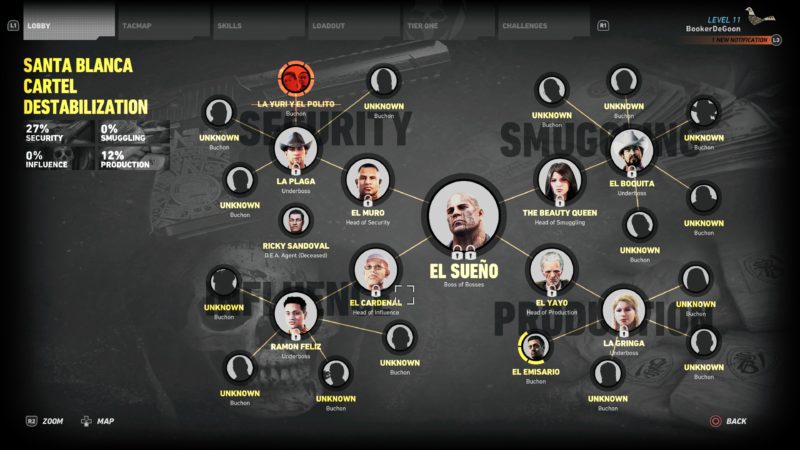

The cartel’s structure is manifested in the game as a web of subordinates, each controlling a different region of the game’s expansive map. Progress toward the leader himself is non-linear, but each region is rated by difficulty-taking on those higher tiers would be difficult without the skills and equipment gained on the lower rungs. Each region is littered with intel on its respective buchons, and the writing makes major missteps here. In one audio log, cartel torturers La Yuri and El Polito have a lengthy discussion about the shape and cleanliness of a dead guy’s dick. These attempts at lighthearted humour read like Ubisoft trying to disengage with the jingoistic narrative they’ve already buried themselves in.

Early in the game, I had to get into an enemy warehouse to take out some processing equipment, another step toward finding one of the buchons. After sneaking my way in, I slipped up. What should’ve been an easy pistol kill went wide of my target, and he alerted the whole base. What ensued was a slaughter, as I mowed down the existing force and the reinforcements called in by alarms. And then it was over, and the cartel forgot about the warehouse. They forgot the slaughter and the American specialists who destroyed their equipment. Wildlands’ Bolivia remembers its conflicts and laments its occupation. At least, Bolivia as a setup-as the narrative backdrop to your chaos-remembers its conflicts. None of the people in it remember a thing.

The same problem expands to your squadmates, who are incapable of describing anyone in the country without using the words “motherfucker” or “shitballs”. They are actively unpleasant to be around and impossible to get away from. As Jack de Quidt wrote for Waypoint, you can’t escape the malice of Wildlands.

Also littering Bolivia are supplies, the tagging of which will likely take up most of your playtime. Supplies are split into four categories, and different skill unlocks will require certain types of supplies. Even early in the game, the high costs of certain skills forced me into grinding some of the higher-reward activities. If the AI and mechanics were anything more than the bare minimum, this wouldn’t be a problem. As it stands, it makes the longer-term experience a repetitive one.

Fortunately, customisation is fantastic. Though face and body options don’t quite reach the heights of Bethesda games, the number of clothing and equipment options on offer make an otherwise bland game feel just a bit more relatable. It could use a system of loadout slots for saving equipment setups, but its otherwise a solidly rewarding series of menus.

All these issues and mechanics lead naturally back to the pitch of Wildlands as a co-op game. Blasting around the world with no regard for the characters is a significantly better time than trying to project any pathos onto Wildlands in solo play. It’s also a welcome reprieve from the insufferable nonsense of the AI squadmates.

But even in co-op, the issues with the game are readily apparent. Wildlands promotes a “freedom of infiltration” approach to missions, but the movement restrictions and underdeveloped stealth mechanics totally limit what you can actually do in the moment. More recently, Ubisoft have added a Splinter Cell crossover mission to the game that has you silently making your way into a camp to meet with Sam Fisher. The initial excitement of hearing Michael Ironside in the classic role wears off quickly against the realisation that Wildlands’ idea of covert operations only extends as far as a suppressor. This isn’t a game that wants you to stop killing, so when it forces you to take the pacifist approach, the mechanics come apart at the seams. What good are the swathes of camouflage options if they have zero impact on visibility? Why bother being stealthy in the first place, in a game with absolutely no risk?

If nothing else, Wildlands has top notch production values. Tonnes of bespoke cutscene and audio work for each of the regions and their associated cartel leaders; painstaking detail in clothing and environment design; and a world that, at least graphically, raises the bar for a map of this size. It’s a technical powerhouse, and smaller details like clouds and weather effects really show that Ubisoft’s developers can pull off some amazing feats on console hardware.

But Ghost Recon: Wildlands is a shame. Ubisoft created one of the biggest and prettiest open worlds in recent memory and filled it with a tone-deaf caricature of violence. Sincerely, the narrative heart of Wildlands is so morally and creatively bankrupt that it’s not worth the volume. The gameplay driving the narrative is tactics-adjacent, but not once does it truly hit the mark. There could’ve been something here; a revival of the Ghost Recon name that brought it back to the tactical gameplay I associate with it. Maybe we’ll get that game one day.