Back in February I wrote an article on how games are made. The article, I hope, delineated how most games are made. In this article, and, perhaps, future articles, I will go into more depth on the first step in game development, story; namely, what it is and its parts. To clarify, this is not a systematic treatment of stories and their various kinds: I’m not qualified to go there. Instead, I want to describe a general order and general purpose of stories.

To begin with, we should distinguish between story and plot. Plot is some event that happens; story is the overarching contextual significance of the event(s). For example, June catches her boyfriend flirting with other women. By itself, this is an insignificant, though interesting, event. We naturally ask why, where, when, and how. Story answers these questions. June met a man who could meet her needs. They dated for a while, until, during their four-month anniversary, she caught him flirting with other girls. They had not discussed an open relationship. He hurt June. After a cold, ambiguous text conversation, they met for coffee and broke up.

Stories give plots meaning; plots without stories, therefore, are meaningless; they don’t go anywhere, they just happen. Stories go somewhere and take plots with them. Walking the rainy streets of New York is an event. Getting mugged while walking the rainy streets of New York might be eventful.

With this distinction in mind, we learn that stories are orderly. By ‘orderly’, I mean stories go a certain way; they have a more or less detectable pattern. While orderliness isn’t the only factor in stories, it is certainly an important one. If there is no order, by which I mean no way one could make sense of things, then the game is a hodgepodge of unconnected, unrelated events. Like Seinfeld, every game would be ‘about nothing.’ There would be no cohesion.

If it’s true that stories are orderly, then what order should they follow? At a most basic level, stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end. If a story had no beginning, we’d have no reference for either the middle or the end; if no middle, we’d have no sense of progress or tension; if no end, we’d assume the story’s still unfolding, with no payoff in sight.

A general order that most stories follow consists of exposition (‘setting up the story’), rising action (or ‘conflict’), climax (‘the highest, most tense point in the story’), falling action (the subsequent, relieving events, lessening the tension), and denouement (or when ‘everything comes together’). From exposition to denouement, the story is moving forward; there’s a sense of progression, beginning somewhere, occasioning stuff in the middle, and tying things together in the end. Space prohibits me from going into depth on each of these parts. If incomplete or unsatisfactory, these are at least helpful categories. With these in mind, we can more sophisticatedly label parts in June’s breakup story and other stories our games might present us.

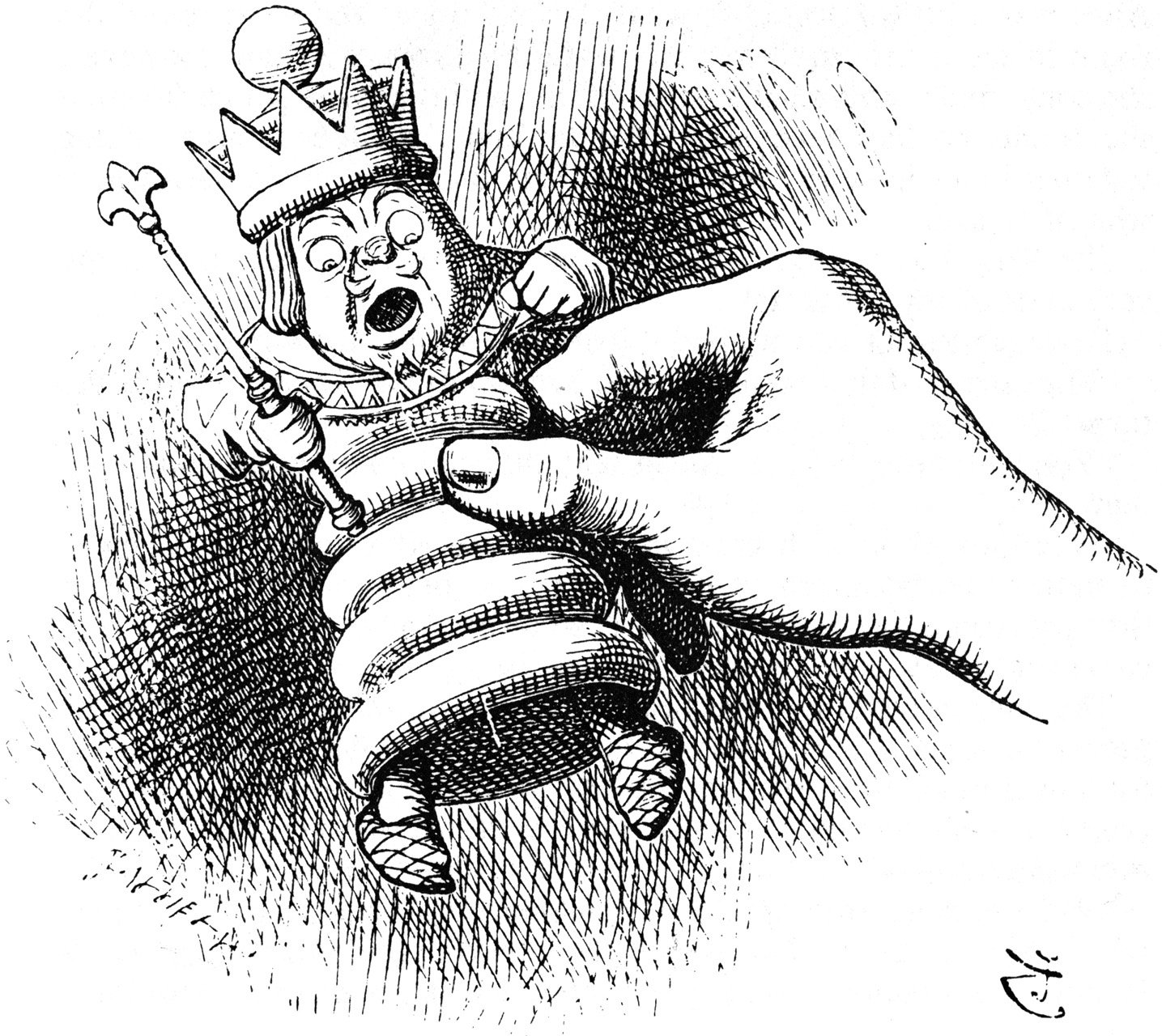

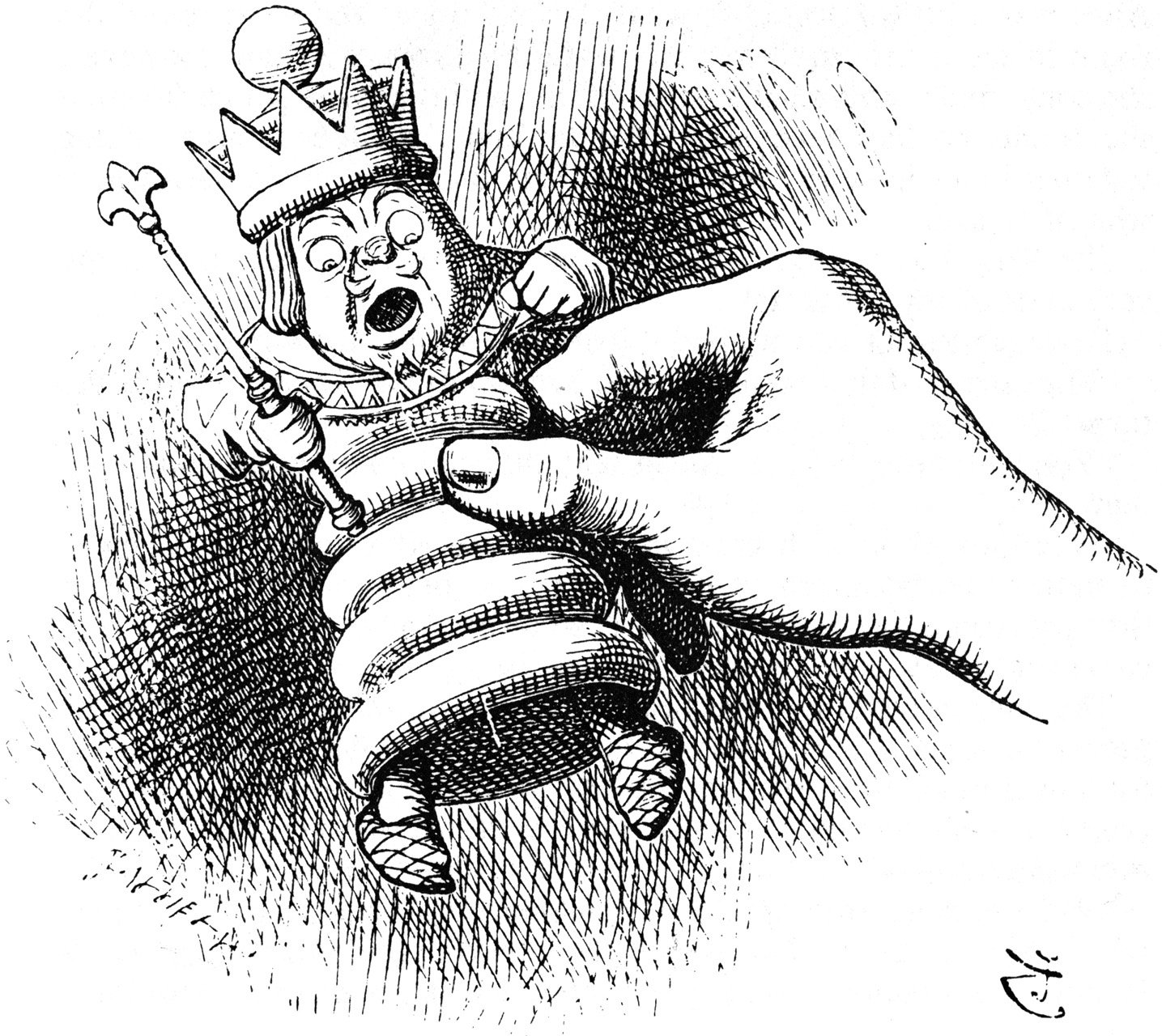

In Through The Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll’s King character offers some helpful advise for storytellers. ‘“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, very gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”’ I hope this piece has helped my readers detect those very parts of a story, its beginning, middle, and end. I also hope to have offered a general purpose to stories, what function they serve and how they’re different from plot. If I have done either of those things, I’ll consider this sub-chapter in game development a success.